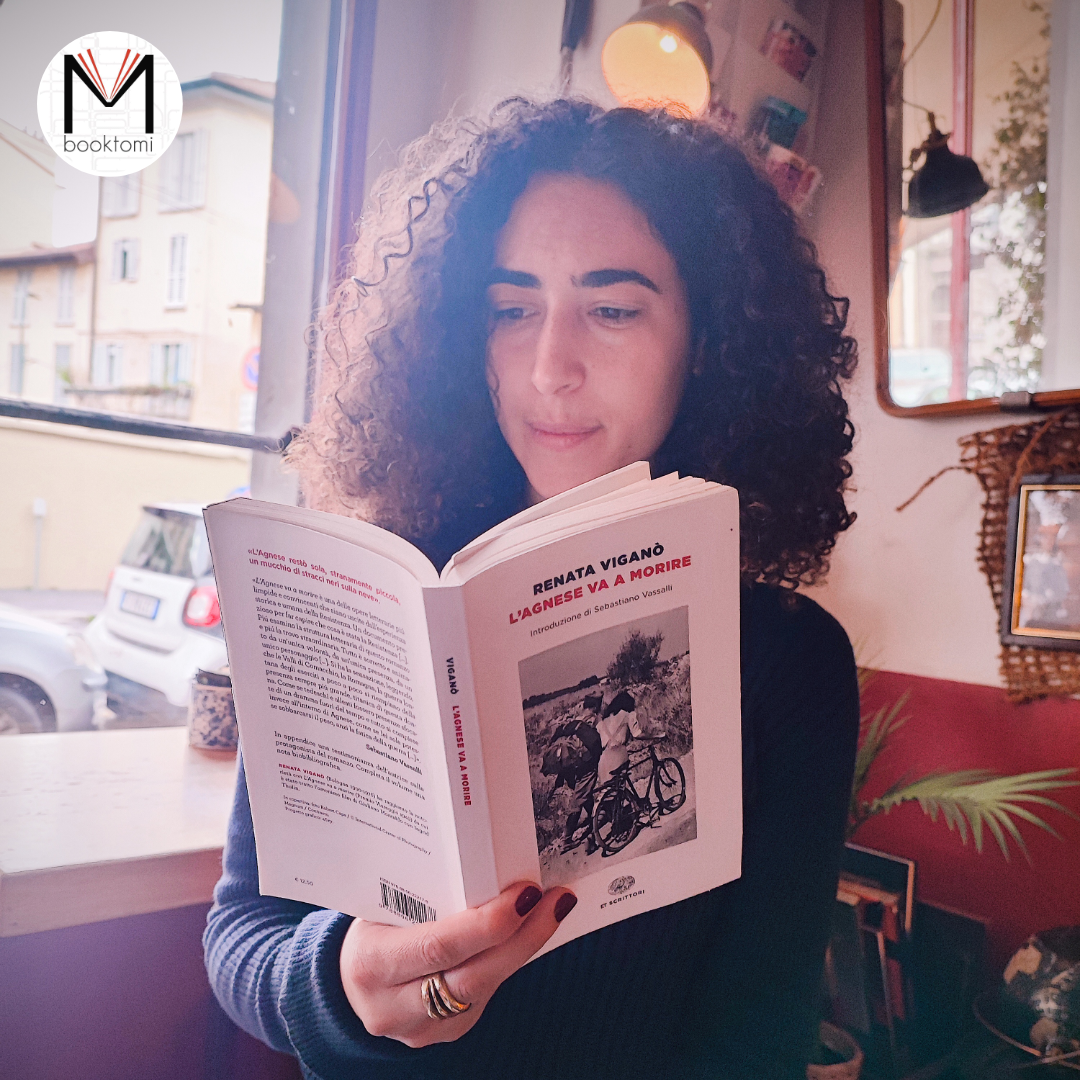

“In front of the fascist house he cleared his throat, picked up the saliva in his mouth and spat on the ground.”

Italy post armistice of September 8th, brothers against brothers, native homeland, a land of contention by foreign feet, and raped by innocent deaths.

The action takes place entirely in the Comacchio Valleys, where History – with a capital H – during the Second World War collides and overwhelms the history – with a lower case h – of a peasant / washerwoman, namely Agnese and her husband she Palita. The day everything changes is that of a German roundup, perhaps following an exposé, in which Palita is forcibly forced onto a military truck. One of those long journeys, all too well known, where very few would return home, and unfortunately Agnese’s husband will not be among them.

Finding herself alone in the world, in her simplicity and if we want ignorance typical of the Italian countryside of the time (the mind goes to the peasants of Fontamara), Agnese will acquire an ever greater social and political conscience and as a woman, in a world where gender equality was not yet conceived.

By reconnecting with some of her husband’s companions, she soon becomes a partisan courier, with increasingly greater organizational responsibilities, and giving her contribution to her history.

The autobiographical traits of the novel with the life of the author are many, and we were very fascinated by her political awareness, a refined thought that allows her to take a clear position not only on the Nazi-fascist action, but also on the political/ soldier of the Allies during the Italian campaign. Equally appreciated in the story is the way in which the soul of the Italians is examined, both in the acts of courage and in the acts of cowardice, on both sides of the conflict.

Born as a poet, the author manages to give shades of poetry in many pages of the text, with the adoption of rhetorical forms that leave the reader surprised, from the “happy fire” that burned the valleys, to the “planes like butterflies” as they dropped bombs on the population.

The book should be brought back to schools as compulsory reading. Let the new generations know what their great-grandparents had to suffer. Make people understand what it means to be at war, hunger, fear and the cost of freedom.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Renata Viganò, L’Agnese va a morire, Einaudi, Torino, 2014 (prima edizione 1949)