“FRIDAY DI-VERSO”

“…surprised about how long I’d lived, still unsure how it was going to end.”

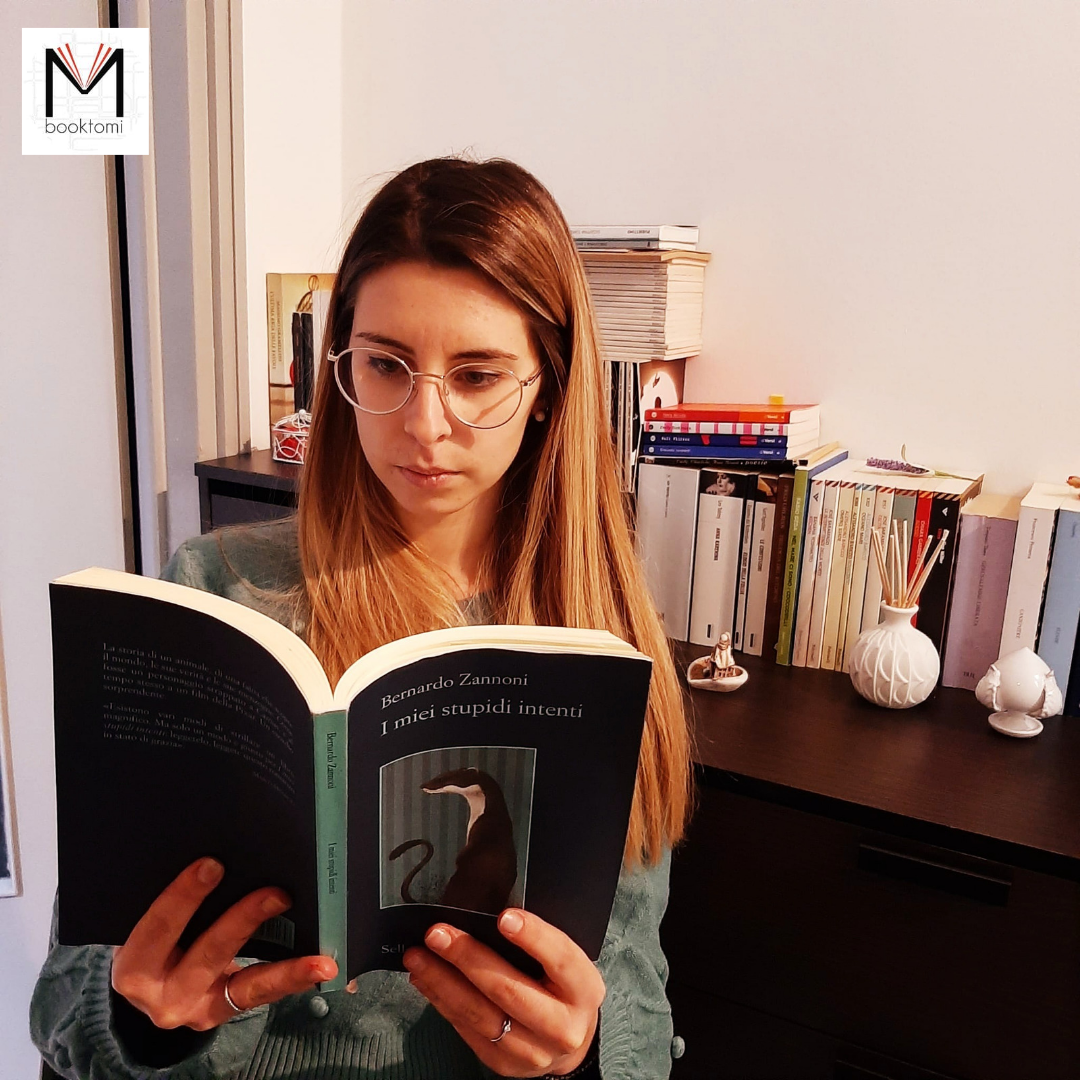

Perhaps a review would be needed for each chapter. Or those scholastic questions of understanding the text, for once without the obscene hassle of a “right” or “wrong”.

Because this, gentlemen, is a book that poses many questions. Starting from the choice of a population of the undergrowth as the protagonist: is it a (black) fairy tale? a satire? an exercise in style? (unpleasant) … Where are we?

We are at the beginning of a life: the life of a little marten called Archy. To immediately put us at ease with the situation, already alienating in itself, the opening of the novel proposes: the widow of a bandit who died a violent death a stillborn puppy four hungry father orphans and half-frozen maternal slaps that gouge out the eyes etc.

It is the law of nature – it seems cruel but right because we are talking about animals; because we are not talking about us. We, we humans are better than that (ha!).

Writing a story of animals is a literary stratagem that brings with it many consequences: it condenses the time of a life into a few seasons, accelerating emotions, traumas, teachings, losses. It stuns us at the crudeness of certain actions, be they good or evil – but does it make sense to talk about good and evil, right and wrong in this zoomorphic universe? And immediately, does it make sense to talk about good and evil? Archy reflects: “I acquitted myself, and made peace with those who had hurt me, because outside our heads, all pain has no weight: because evil does not exist.”

What is then truly disarming is the continuous mixing of humanity and animality, eternally shared, in an ambiguous balancing act that always succeeds in the noble aim of making the reader uncomfortable. It is literally uncomfortable to read, since one no longer knows how to place oneself: in the free instinct of the animal or in the rational conscience of man? And what virtue do we axiomatically associate with awareness and knowledge? Is it power or illusion? Does knowing save us or damn us? Does the animal that aspires to the role of child of God by setting aside its own nature win or lose Paradise?

Do the concepts – Love, Death, Time, God – free you from fear? “Are the words hot?” Anja asks Archy, who has now passed from the role of pupil to that of pater familias. They heat what they can, one might answer, but they burn much more. Hoffmansthal’s Lord Chandos would say that they burn the possibility of describing an inner world of immense turmoil and unspeakable trifles – words not only arm an intellect, but can also limit it. Yet, what to do? Return to the wild animal life, to the preludes of civilization? The author proclaims the supreme gift and the lowest boundary of the animal: to live in the instant. It is in the present moment that the only possible peace is found, it is in the present moment that memories and hopes are lost. There seem to be no solutions or compromises – the Luci sang: “There is nothing to say, nothing to explain, nothing to understand, there is only to exist, to let it go …”

And after so many questions left open, we close with a minute but fundamental certainty: being made uncomfortable by a young author at his debut is a privilege; feeling the center of gravity shift and lose balance in the clarity of a sentence constructed without presumption, white in its exactness, makes you lift your hat and bow your head in a slight bow of genuine gratitude.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Bernardo Zannoni, My stupid intentions, Sellerio, Palermo, 2021