“…I had never been able to find anyone suitable for the spaces that were created within me.”

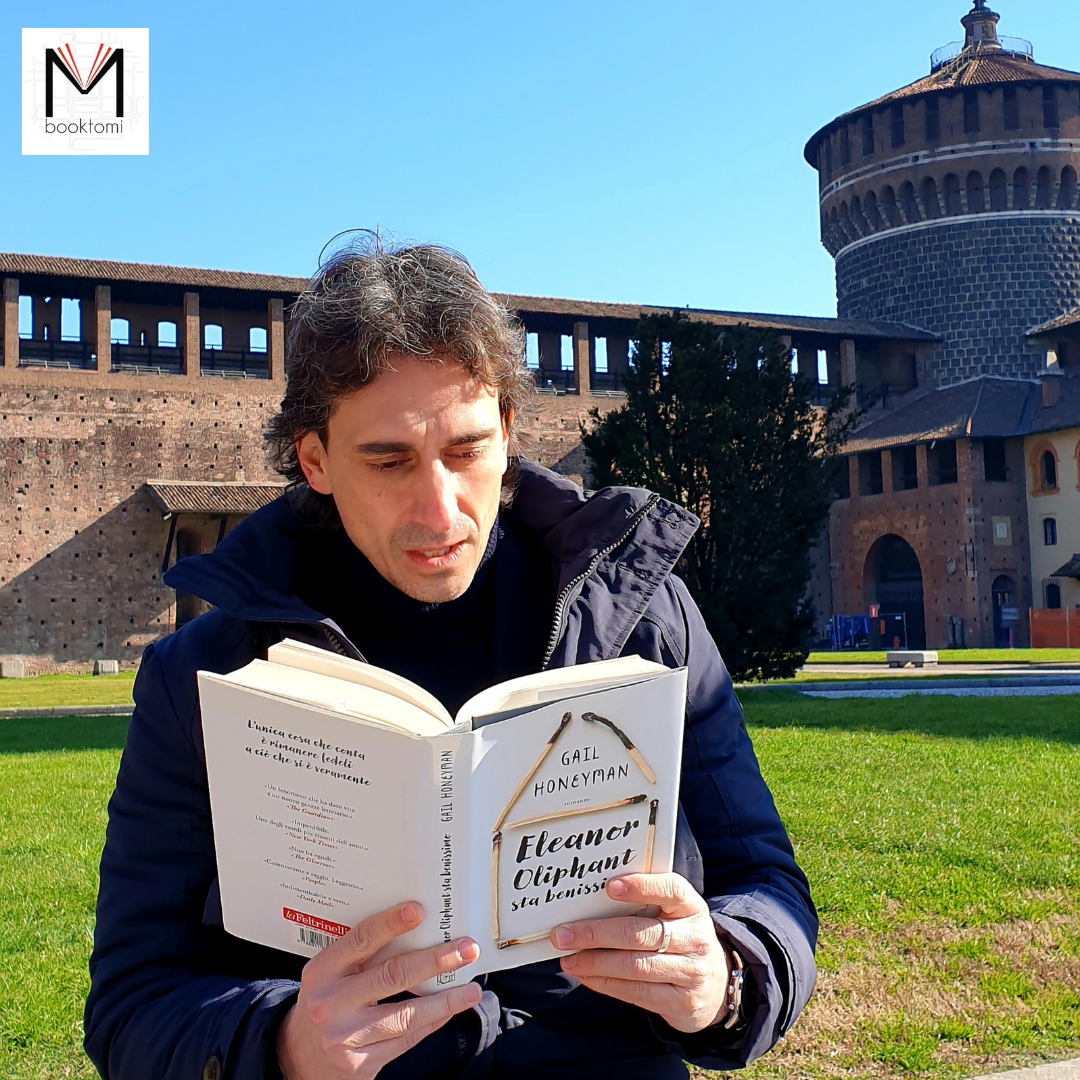

“Eleanor Oliphant” is fine has been a resounding editorial success in recent years; we read it with care and curiosity to find out the reasons and we think we have found some.

Eleanor Oliphant is a sober thirty-year-old, with an anonymous “office job” which she has been fulfilling promptly and without any trace of enthusiasm, five days a week, for nine years. On Friday nights, she buys two bottles of Glen’s and tries to survive the weekend. On Monday she starts again.

Eleanor Oliphant is perfectly fine by herself: any intrusion from the outside world is inconvenient and unpleasant, ultimately avoidable. Yet – is it really possible (or desirable) to avoid life?

There are two Eleanors.

There is a misplaced, unpleasant, insipid Eleanor, mostly indecipherable. It is what colleagues make fun of when they can’t help but avoid it, with no room for understanding or empathy.

Then there is the Eleanor told by Eleanor: the one that she always says what she thinks (even when frankly no one is interested in hearing it), genuinely unaware of the most elementary rules of sociability, barricaded behind a liturgy of apparently incomprehensible habits.

The reader is granted the privilege of knowing both, of identifying with the stinging (and somewhat banal) sarcasms of colleagues as well as smiling at the undeniable linearity of Eleanor’s arguments. If we were colleagues, would we react differently to certain answers? Maybe not. But what we have in hand is a VIP pass – and that makes all the difference.

Why do we find ourselves thinking: how many invisible solitudes have we crossed without recognizing them? How many oddities have we dismissed as ridiculous without benefit of appeal? How many silences have we not been able to listen? And it is not a question of always and in any case being burdened with the ills of others, the complications of others; it’s not even about seeing them. It is a question of suspending the time of judgment, of allowing oneself more relaxed, more inclusive, less ruthless and definitive margins of evaluation.

The path that Eleanor takes to survive the traumas of her history passes precisely through the encounter with individuals capable of a similar relaxation: of views, of times, of possibilities granted to the other-than-self.

Telling a loneliness, the habit of detachment as an armor in the world, but also the unpredictability of opportunities – all human – to get rid of it: this is what Gail Honeyman does by painting Eleanor Oliphant with naked kindness. If the success of this book has been so transversal then perhaps it is because it speaks to those who recognize themselves in that devastating anesthesia of feelings that can become loneliness but also to the army of the alleged “normal”; speaks to the tortured and the torturer, to the keeper of pain and to his unwitting spectators.

She says the wise: be kind, because every person you meet is already fighting a battle you know nothing about. With simplicity and irony Gail Honeyman tells one of these battles, how to win it and how to help those who are fighting it. And then, avoiding the personalisms and snobbery of some criticism, long live Eleanor Oliphant’s success.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Gail Honeyman, Eleonor Oliphant is completely fine, Garzanti, Milano, 2018

Original edition: Eleonor Oliphant is completely fine, HarperCollins, Milano, 2017